Two years ago, Politico published a draft opinion indicating that the United States Supreme Court would strike down federal protection of abortion rights. Thousands of people hit the streets, yelling “We will not go back!” and “My body, my choice!”, flashing coat hangers to signify the dangerous future toward which the country seemed to be careening. Protestors hoped to show support for abortion rights and sway the court’s majority.

On June 24, 2022, the official decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization was released. Despite the tireless work of pro-choice activists, Dobbs overturned two landmark court cases—Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey—and nearly 50 years of precedent protecting a person’s right to choose. The repercussions were immediate: 13 states had trigger bans in place to outlaw abortion should Roe ever be overturned.

Over the past two years, the assault on reproductive freedom in the United States has not slowed. Today, the Center for Reproductive Rights reports that 28 states have outlawed, are hostile to, or do not protect abortion. The Supreme Court is currently considering whether to limit access to mifepristone, a medication used in more than 60 percent of US abortions. As abortion bans and restrictions multiply and abortion clinics close, mifepristone is an essential tool for preserving abortion access. It can be prescribed without an in-person medical visit by a professional other than a doctor and can be mailed to patients, making it accessible to persons living in rural areas and states where abortion is restricted. While early reports indicate the Court is skeptical of restricting mifepristone, some questions from conservative justices signal possible future pathways for limiting access to medication abortion. The case is yet another attack in an unrelenting war against abortion access.

As the matter of abortion access shows, movement toward gender equality is not simply a matter of two steps forward, one step back. Most measures indicate that progress toward gender equality stalled beginning in the 1990s. For instance, mothers are now more likely to be out of the labor force than they were two decades ago, a trend accelerated by the increased childcare demands of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The power that makes progress happen—the relentless strategizing and work of movement organizers fighting real-world constraints and a well-resourced opposition—is often invisible to the people who enjoy the fruits of their labor. Until recently, many people still believed that the moral arc of the universe bent toward justice and that the occasional hiccup was just that. But two years ago, the Dobbs decision catapulted us backward nearly 50 years. Dobbs and other recent events—Donald Trump’s 2016 victory, the fierce opposition to the Black Lives Matter Movement, pandemic-fueled anti-Asian hate, and the surge in anti-trans legislation—teach us that progress is not unidirectional. It relies on commitment, time, and work.

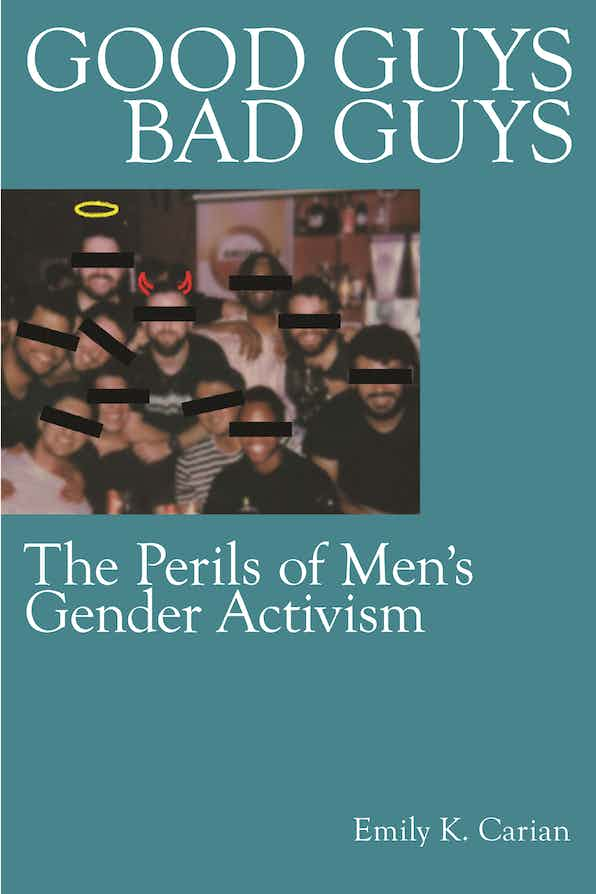

Organized backlash movements, like anti-abortion groups, contribute to the stalling out of the gender revolution. But another part of the story is the failure of feminist allies to bring to bear their resources and power in service of gender liberation. Four-in-ten American men consider themselves feminists, but this hasn’t reignited the gender revolution. I uncovered why in my forthcoming book, Good Guys, Bad Guys: The Perils of Men’s Gender Activism. The men I interviewed identified as feminists to bolster their moral sense of self, well aware that others might perceive them as privileged because of their gender. Becoming a feminist allowed them to feel and signal to others that they were exceptions to the rule that men are the “bad guys.” Yet this rarely translated to meaningful activism because simply identifying as a feminist was enough for them to feel like and portray themselves as good men. Despite volunteering for a study of feminist men, nearly half of the men I interviewed did no activism beyond posting the occasional opinion online, signing petitions, or attending a march. Feminists recruit men to the movement so that men can use their disproportionate power, resources, and status to bring feminist goals to fruition. When men can use feminism in service of a self-centered identity project, they don’t need to do activism.

When men did do activism, their work often centered the concerns of privileged people like themselves. For example, they organized groups where men could discuss the tensions of being an ally. Instead of dismantling their privilege for the liberation of others, feminist men focused their efforts on learning how to live with their privilege.

While men’s feminist identification is symbolically significant for feminism as a movement, men’s allyship is less than ideal. One in five American men have been involved in an abortion. It will take more than their posting online or their participation in a march to confront the well-organized anti-abortion movement slowly but deliberately chipping away at abortion rights in this country. Real progress requires that men allies be in the trenches, organizing for reproductive justice. As we approach the two year anniversary of the Dobbs decision, feminist men must ask themselves what feminism does for them and what they in turn can do for the movement and gender liberation.

Emily K. Carian is Assistant Professor of Teaching in the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Irvine. She is co-editor of Male Supremacism in the United States: From Patriarchal Traditionalism to Misogynist Incels and the Alt-Right.

Six Classics of Queer Literature

Six Classics of Queer Literature