1. In Scarred, you describe your journey traveling to twenty countries in just over a year. Can you describe what motivated you to undertake so much travel, and how your concerns about your pain factored into your decision to go?

When I first set out to travel, I didn’t know that I was going to end up traveling to twenty countries. There were several countries that I knew I was going to visit, like where my family was, or where my writing residency and workshop took place, but the rest was up in the air. But I knew I wanted to travel, to take a break from it all. I was feeling frustrated with where I was with my life, personally, professionally, and also politically—especially with what was going on in this country when Trump won the election. I suppose when the fight or flight response kicked in, I chose the “flight” mode instead, and quite literally. So there I was traveling and hoping that it would make me feel better.

2. What was your favorite place you visited? How did your experience in this place help you understand pain differently, and did it ever answer your question, “Can travel really heal?”

One of my favorite places to visit was Nepal. That was probably evident from how I wrote an entire chapter based on my experiences there. I stayed at a meditation ashram called Osho Tapoban. There I learned a meditation technique called “no-mind” meditation. It basically takes us directly to our body to bypass our mind. The technique allows me to resurface the deeply buried emotions and to transcend them. And this technique of working with my body, and without the story helps transform my pain. Sometimes language limits how we can express, experience, and transform our emotions. We need to work with the body directly, without being trapped by our own stories of why we feel sad, or how we can deal with it, etc.

Travel can heal. But it depends on how we travel. If we travel only to replicate what we do at home, speak the language, eat the food, or do the routines we do at home, traveling is not going to heal us at a deeper level. But when we can create new routines, new habits, and eventually a new body, we can heal—we can live in a new body, so to speak. Having said that, I want the readers to know that healing should not be our ultimate goal in life. The goal, at least for me, is to understand that we will continue to live with pain, maybe in different forms and intensities throughout our lives, and therefore we want to explore how to live with and carry pain differently.

3. In your book, you talk about “perceiving” pain differently—not as something to move through, but as something we “carry with us.” How does society teach us to think about and deal with chronic pain, and what are you proposing we do differently? How did traveling help you come to this conclusion?

In our society, we are bombarded with so many methods, medicines, and meditation audios to manage and avoid pain. Sure, I meditate and take medicine as needed, too. But the approach or the story about pain as something that we need to avoid, to control, needs to be changed. What I’m proposing here is that we first accept that pain is here to stay. If we are going to live with it anyway, why not make our experience with pain more enchanting? How can we carry pain in a more comfortable way? If pain were a backpack, how can we adjust how we carry it, so it feels more comfortable for us?

When I suggest that we perceive differently, I am not saying that we should simply think positively. Not at all. I don’t want us to dismiss our pain. On the contrary, I invite the readers to honor the pain, and to perceive differently, by asking how has our society taught us about how to perceive? Does it further create pain in our lives? How can we perceive in ways that do not provoke even more pain and that liberate us from the shackle of societal gendered norms?

In the book, I talk about four things that I propose we do so we can live with pain differently: 1) to perceive differently; 2) to work with the body; 3) to practice feminist enchantment in our daily lives; and 4) to have emotional contract.

Traveling helps me get to this conclusion because as I was traveling with pain, pain gave me a lens to see things differently. My pain pushed me ask different questions that I would have not asked, and do different things (like a meditation retreat in Nepal) that I would have not done, had I not felt pain.

4. You ask in Scarred, “How can I work with my body to process pain?” Can you talk about what you mean, and what you uncovered about the ways we process and think about pain in our bodies?

In our society, whenever we feel sad, people would jump in and ask us, “do you want to talk about it?” It even feels like we have to talk about our feelings, if we want to feel better. But after doing the meditation that specifically teaches us to bypass our mind, I began to understand that words may get in the way of us actually feeling and transforming our emotions.

Nowadays, whenever I feel anxious, or other strong feelings in my body, my first go-to-activity is not to pick up the phone and talk to someone. I would turn on some music and dance, or walk while being focused on what I see, and try not to be in my head. I try to return to my body, but without telling stories about why I feel sad, or what I can do about it. Surprisingly, these simple activities would lighten my feelings a little bit. Ideally, I can do the “no-mind” therapy at home, too, but it is harder to do it at home/by myself, because it involves a lot of screaming that may scare my neighbor. I remember the meditation teacher in Nepal told me that there was a woman in Texas who would come all the way to Nepal because she couldn’t do the “no-mind” meditation at home. Now I understand what he meant.

5. In order to shift one’s relationship with pain, you describe a daily embodied practice that you call “feminist enchantment.” What does enchantment look like to you? How can others dealing with pain adapt this practice in their daily lives?

Being enchanted by something means that we suddenly forget about everything, including our pain, and be consumed by this enchanting thing. We become absorbed into its magnificence, its beauty. To be enchanted for me also means that we feel alive inside, we feel full, and we can feel the erotic energies running through our bodies. It means to return to our natural state of being playful. For me, because I live in Hawaii, I try to watch the sunsets every day. That’s my one thing that I do to feel enchanted. It’s amazing how the color, the shape, and the cloud are never the same. They put on a different show every day, including when it’s cloudy or stormy.

When we feel enchanted, it’s as if we get this permission slip that says, “it’s okay. You can take a break from your pain now.” Sometimes we get ten minutes of enchantment, sometimes ten seconds of enchantment. But that’s okay. Those ten minutes or ten seconds help us carry pain better, than if we only feel pain 24/7. So, whenever it is still possible, try to do one thing, or eat one thing, or see one thing, that will bring us moments of enchantment every day. What would that be for you? I think this is the whole point of the book: rather than telling the readers, “Here are the 100 things you should do,” I say, “this is what works for me. What about for you?”

6. Your book takes the deeply feminist stance that the personal is political. What programs and policies does our government need to reform so that we can carry pain in a more life-sustaining way?

There are so many things that our government, our workplace, our neighborhood, and our family can provide us with so we can feel supported and live with pain differently. But we can start with three things.

The first is universal and accessible health care that includes mental health care. NPR has a special series, “Bill of the Month” that shares people’s stories about their outrageous medical bills. And this worries me. We can’t live like this. We need programs and policies that will make people be and feel better, regardless of their employment status, or class, gender, sexuality, and racial backgrounds, or health insurance! The pandemic shows how bad and unequal our healthcare system is. Improving our healthcare system and making it equal and accessible across the board is the first and most important thing that we need to address.

We also need to address parental and family leave in this country. We cannot be the only OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development)-member country or one of the few countries in the world that doesn’t have a national paid parental leave policy. Other countries such as Iceland gives each parent six month leave, for a total of twelve months for both parents. There is a limit to how much a person can receive, but within that limit, a person can receive up to 80 percent of their average income. We need paid parental leave to support parents, babies, and coworkers. If parents don’t feel supported, and if babies are not supported from the moment they are born, how can we say that we care for them?

Lastly, we need better new-immigrant programs that could make immigrants feel more supported and welcome in this country. This anti-immigrant sentiment is really hurting us as a community, as a nation. In Iceland (one of the countries I talk about in my book), they have legal counseling services for new immigrants, they even have women’s circle programs to support new immigrants feel more at home in the new country.

All of these programs are important: if we don’t have national programs and policies that support our physical and mental health, our family, and new members of our nation, then how can we say that our government really cares about us? Ultimately, pain is never only personal. It is also social, structural, and political. No matter how much pain-killers or meditation classes we take as individuals, if the political environments are not supporting us to thrive, we can only go so far in addressing the pain in our lives. It’s time for a change.

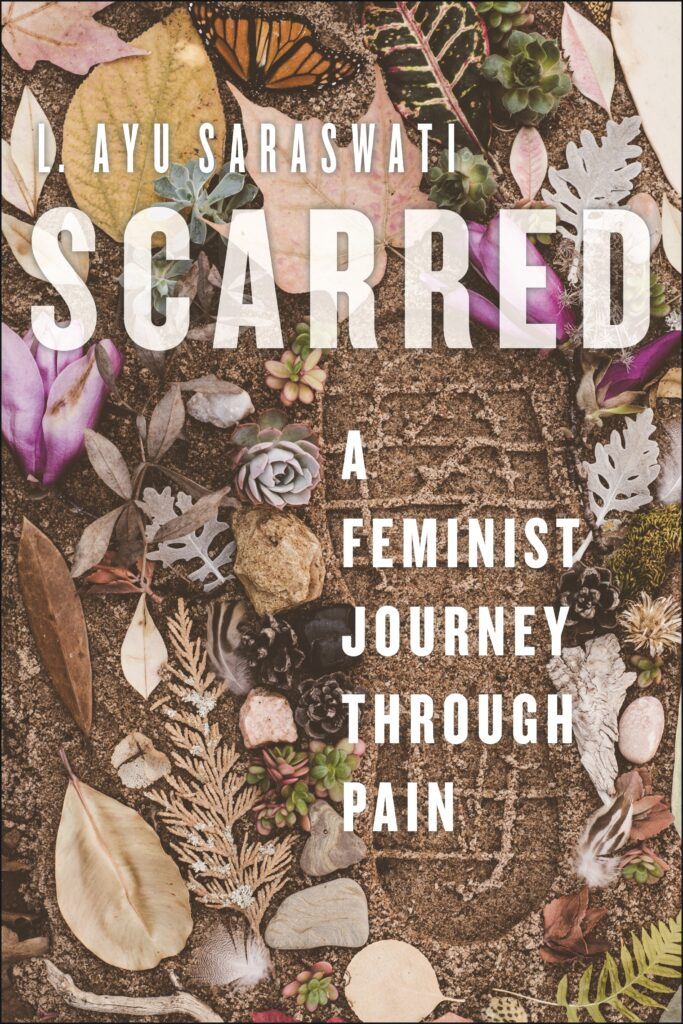

L. Ayu Saraswati is Professor of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Hawai’i, Mānoa. She is the author of Pain Generation: Social Media, Feminist Activism, and the Neoliberal Selfie and Seeing Beauty, Sensing Race in Transnational Indonesia, which won the 2013 National Women’s Studies Association Gloria Anzaldúa book prize. She is also the co-editor of Introduction to Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies: Interdisciplinary and Intersectional Approaches and Feminist and Queer Theory: An Intersectional and Transnational Reader.

Six Classics of Queer Literature

Six Classics of Queer Literature