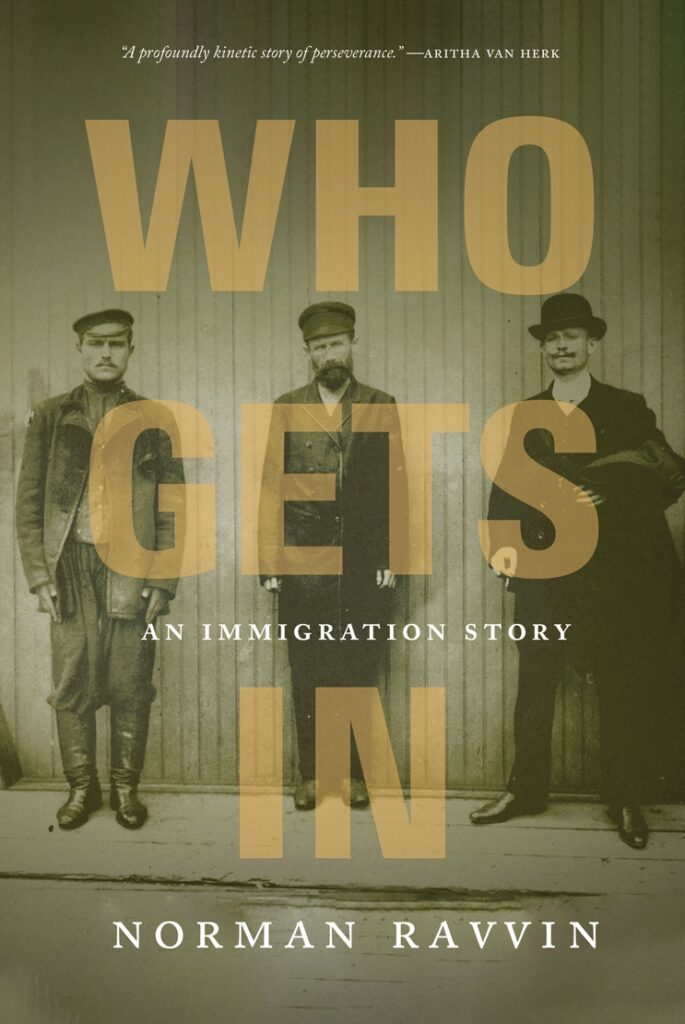

At a recent launch for my memoir Who Gets In: An Immigration Story at Canada’s National Archives in Ottawa, two young attendees told me they’d attended because they were in the middle of their own immigration story, their goal being full Canadian citizenship. Immigration is headline material in the United States as it is in Canada, but we often get a view of its chaotic character: struggles to get across borderlands, skirmishes with custom patrols. Meanwhile, the subject is kicked like a hot potato from one side of our ruling class to the other.

My Polish-born grandfather was, in important ways, like the young people I met in Ottawa. He was not a political or economic refugee; he was leaving a place where he was well established with deep family and cultural ties. His decision to emigrate in 1930 was made well in advance of dark events to come for Jews in Poland. He was part of a longer-term pattern of leaving, of eastern and southern Europeans who responded to the pressure of economic and social shifts in their home the way a seismograph senses the early tremors of an earthquake before it destroys the status quo. Both a family memoir and a far-reaching portrait of immigration in the early 1930’s, Who Gets In tells an old story that retains remarkable resonance for newcomers and those who encounter them today.

In order to make his move, my grandfather had to lie to the Canadian Immigration Branch. He told them he was single at a time when this was one of the few categories of Jewish males allowed, with a relative’s sponsorship, into the country. His struggle to bring his young wife and two small children after him would consume him for nearly five years.

A shift toward nativism, race-baiting, and rising restrictions on immigration characterized Canada and the United States in the latter half of the twenties and the early thirties. Both countries shared the impact of Depression and wheatland droughts that made the late years of western settlement a calamity as people newly- and long-placed on the land abandoned farms, small towns, and villages.

Increasingly, Canada’s immigration regulations mirrored those in the United States, though Canada was less overt about its use of quotas for specific national or religious groups. Newcomers from the United Kingdom and the U.S were always welcome, as were people willing and able – “bonafide,” as the era’s lingo had it – to go west as agriculturalists.

Who Gets In addresses these broader trends but tells its story from the bottom up, in my grandfather’s new home in central Saskatchewan among Jewish farmers. In early 1932, he began to write to anyone who might help him solve his family’s breakup. He started with JIAS, the Jewish Immigration Aid organization that had offices in Winnipeg and in Montreal. He moved on to lawyers who had inserted themselves into the immigration game, and then to provincial and federal elected officials, up to the Minister of Immigration in Ottawa, who had the Prime Minister’s ear.

My grandfather’s immigration struggle in the first half of the thirties had a unique character, governed by a conservative Prime Minister and elected officials who had their own ways of dealing with the checkerboard of ethnic settlement on the Prairies. He had to struggle with a racially biased civil service whose raison d’etre was to apply cruel immigration rules. Using my grandfather’s letters, I tell the story from his perspective. This provides a different view of what is known in Canada as the “None is Too Many” period, during which it’s understood that Jews were barred from accessing permits to enter the country. This rubric better describes the later 1930s and the status quo that held until a postwar economic boom and the impact of the Holocaust led to an influx of survivors after 1948. As I pursued this story in Jewish and national archives, I discovered that an individual’s willingness to stick to his goal, and the right people’s influence, could bring about surprising, though never guaranteed outcomes.

The reality my grandfather confronted is best conveyed in a passage from Who Gets In, which describes the “Kafkaesque aspect of these Canadian decades rarely acknowledged: a system of authority, when called upon by an outsider to explain itself, cannot do so. Even more importantly, a system that seems to be an expression of total authority—cynical and unrelenting—is no such thing. It is always in danger of being undermined, some links weakened to the extent that the whole thing rattles apart. This is another point at which the “None is Too Many” rubric obscures the story that I want to tell. Had my grandfather heard of such a rule regarding Jews entering Canada from his homeland—and surely he did not—he would not have heeded it.”

If I could catch up with the young couple I met in Ottawa, I would be glad to hear if my grandfather’s story put their own individual efforts into sharper view. In the face of what must seem like overwhelming bureaucracy, against a backdrop of heightened immigration debates, I hope they’d be comforted by his shared struggle and his ultimate success.

Learn more in Ravvin’s eye-opening account of the Jewish immigration experience in the 1930s, and one man’s battle against anti-Semitic immigration policies.

In 1930, a young Jewish man, Yehuda Yosef Eisenstein, arrived in Canada from Poland to escape persecution and the rise of Nazism in the hopes of starting a new life for himself and his family. Like countless others who made this journey from “non-preferred” countries, Eisenstein was only granted entry because he claimed to be single, starting his new life with a lie. He trusted that his wife and children would be able to follow after he had gained legal entry and found work. For years, he was given two choices: remain in North America alone, or return home to Poland to be with his family.

Born from years of archival research, Who Gets In is author Norman Ravvin’s deeply personal family memoir, telling the story of his grandfather’s resolute struggle against xenophobic and anti-Semitic government policies. Ravvin also provides a shocking exposé of the true character of nation-building in Canada and directly challenges its reputation as a benevolent, tolerant, and multicultural country.

Who Gets In is published by University of Regina Press. A little house on the prairie with big ambitions, University of Regina Press (URP) publishes books that matter—in both academic and trade formats. Their non-fiction trade books tend towards the hard-hitting, while most of their scholarly titles are accessible to non-specialists. They endeavour to develop writers into public intellectuals, encourage debate, and inspire young people to study the humanities by publishing books that are both seen and relevant.

Six Classics of Queer Literature

Six Classics of Queer Literature