Oneka LaBennett is the author of Global Guyana: Shaping Race, Gender, and Environment in the Caribbean and Beyond.

The nation of Guyana is sometimes literally left off maps of Caribbean countries. You ask in your book, “why Guyana, and why now?” What has propelled the nation of Guyana onto the global stage?

If we are concerned with the economic, environmental, and social costs of fueling our cars and heating our homes, we need to pay attention to Guyana. Since ExxonMobil’s 2015 discovery of a supergiant oilfield off its shores—one of the most valuable petroleum and natural gas findings in decades—it has transformed into the world’s fastest-growing economy. The significance of Guyana’s oil boom cannot be overstated. Within seven years of that initial 2015 discovery in the country’s Stabroek Block, ExxonMobil made a string of additional discoveries, raising Guyana’s recoverable oil and gas potential to nearly eleven billion barrels—about a tenth of the world’s conventional discoveries. The amount of petroleum that stands to be recovered off Guyana’s coast is unmatched across the globe; experts suggest it will replace Kuwait as the largest oil producer per capita. The country’s transformation into an “oil hotspot” has garnered international attention from industry insiders and geopolitical observers. The oil boom has also brought with it the threat of war: In a move to annex Guyana’s oil-rich territory, Venezuela is amassing troops along the Guyana/Venezuela border and is attempting to claim two-thirds of Guyana’s territory (that’s most of the country!). A regional war between these two countries would destabilize Latin America and the Caribbean, and the U.S. government has already taken an interest. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken affirmed the United States’ “unwavering support for Guyana’s sovereignty”over the disputed territory, and both The Guardian and the Associated Press reported that the U.S. agreed to provide military assistance to Guyana in the form of aircrafts, drones, and radar technology.

While Guyana’s oil has made headlines, sand extraction in this country and elsewhere remains the worldwide crisis that nobody has heard about. Guyana has been quietly replenishing beach sand in other Caribbean tourist-dependent nations since the 1990’s. So, if you’re sunbathing on a powdery white sand beach in Jamaica, you may in fact be relaxing on Guyanese sand.

As the site of both high-profile oil extraction and invisible sand mining, the nation is becoming a generative prism through which we can radically reformulate how we understand the dynamics of capitalism and ecology in the Americas. And across all extractive industries, we find devastating effects for women and children, including sex trafficking, contaminated water, and insufficient food supplies. Guyana has something valuable to teach us about the interplay between violence against women and environmental catastrophe.

You talk about how the New York Times reported on the Guyanese oil boom, and how various television shows—HBO’s Lovecraft Country, Netflix’s Indian Matchmaker, and National Geographic’s Gordon Ramsay: Uncharted—depict Guyanese people. How is Guyana portrayed in the Western media?

Guyana is everywhere and nowhere in reductive representations across American newspaper articles and popular television programs. In the wake of the oil discovery, a now infamous front page New York Times article represented Guyana as a “vast, watery wilderness.” The article’s marred depiction was pointedly critiqued by Guyanese, who took offense at its descriptions of children who “play naked in the muggy heat” and of Guyanese workers assumed to have a lackadaisical attitude towards safety on Exxon’s oil rigs. The article portrays Guyana as a backwater, stuck in the past.

On television, HBO’s Lovecraft Country portrayed an Indigenous Guyanese intersex character being ogled in a full nude shot before being summarily murdered by the show’s protagonist. Netflix’s global hit, Indian Matchmaking, represented the only Guyanese woman in the series as a misfit who was ill-matched with “respectable” Indian suitors because of her social frivolity and independent nature. In one scene, she orders alcohol on a date, which turns off a young man of Guyanese and Punjabi ancestry, and her mother wonders if all of her years spent practicing Bollywood dancing distracted her from pursuing a partner.

If Guyanese are annihilated in Lovecraft Country and unmarriable in Indian Matchmaking, they are exotic and hard to reach in National Geographic’s Gordon Ramsay: Uncharted. The celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay presents Guyana as among “the most incredible and remote locations on Earth” (even though it is located at the northern tip of South America, and there are direct flights to the country from New York, Miami, and Houston). In Uncharted, Guyana is depicted as a dense, savage frontier, brimming with an exotic but treacherous food culture. On his trek to the country’s interior, Ramsay first travels by plane, jeep, and boat. He then boards a helicopter from which he “channels his inner Tarzan” and repels down to a beach to meet an Amerindian fishing guide. The Tarzan reference situates Ramsay as a neo-colonialist and mirrors the pillaging referenced in Lovecraft Country. By literally stepping over the coastal region where the nation’s vibrant, interethnic food culture thrives, Ramsay promotes a notion of Guyana as little more than rainforest and menacing, if tasty, eats, while casting Indigenous Guyanese as quintessential exotic others.

Across all of these representations, nuanced portrayals of Guyanese people’s cosmopolitanism are nowhere to be found. In fact, Guyana has an outsized presence in America’s largest city—New York. It is a country of less than 800,000 people but it has experienced a massive out-migration. Guyanese represent New York City’s fifth-largest foreign-born and third-largest Caribbean-born group. And the country has long been at the center of global capitalism—the book tells this story.

In your book, you put into conversation the Barbadian stereotype that Guyanese women are homewreckers, with the music and persona of the popstar Rihanna, whose mother is from Guyana. Do you think this stereotype represents global gendered racializations of Guyanese women?

I do. Guyanese women are marginalized at home, exoticized within the region, and rendered nearly invisible beyond. If, for example, we look at the TV show Indian Matchmaking, we see colonial-era stereotypes of the Indian indentured women who journeyed to Guyana transplanted onto Nadia, the Indo-Guyanese contestant. These tropes frame these women as dangerously independent, lacking in respectability, and headstrong in comparison to their “more respectable” Indian counterparts. These negative stereotypes pigeonholed indentured women across two continents—in India as they boarded ships to British Guiana, they were, by virtue of their castes, their unmarried status, and the regions from which they came, stigmatized as sex workers, troublemakers, and rebellious women. These pernicious brands followed them to British Guiana, even though, contradictorily, in the colony they were cast as more subservient than Black women. In the colonial period, women of African descent were represented as the opposite of the dutiful Indian housewife—there, it was Black women who were pegged as headstrong and too independent. And the supposed differences between women from these two ethnic groups framed Indians and Blacks in Guyana as incompatible. The book tells the story of intermarriage between Black and Indian people in Guyana with the example of my great-great grandparents, an indentured woman from India and an Afro-Guyanese man, who had a child when such a union was deemed taboo by British colonial officials. These officials stood to benefit from keeping formerly enslaved Africans and Indian indentured laborers at odds with each other.

When we look at the Barbadian stereotype of Guyanese women as homewreckers, we can unpack these stereotypes of Guyanese women that have endured from the colonial era. Intersectional race/gender formations and migratory processes come to a head in Guyana in ways that we don’t usually consider. Rihanna is known primarily as a Bajan or Barbadian superstar. But her mother, Monica Braithwaite, and her maternal grandmother are Guyanese. In fact, Rihanna credits her maternal kin with shaping her worldview and with inspiring her cosmetics empire. When we look into Rihanna’s family ties in Guyana, we begin to see that her family story is part of a long history of intermarriage between Bajan men and Guyanese women. These familial ties are connected to global racial capitalism. After slavery ended, Barbados had a large labor force, but a dearth of land. Bajan men began migrating to Guyana to find work, and they often married Guyanese women while they were there. This started a long process of intermarriage between the two countries.

In interviews, Rihanna compares the treatment of Guyanese women in contemporary Barbados to that of Mexican immigrants in the US. They have both faced threats of deportation, with immigration agents separating mothers from their children. In an interview with Afua Hirsch in British Vogue, Rihanna says, “The Guyanese are like Mexicans in Barbados…I know what it feels like to have the immigration come into your home in the middle of the night and drag people out. My mother was legal…but let’s say I know what that fight looks like…I was probably, what, eight-years-old when I experienced that in the middle of the night. So I know how disheartening it is for a child—and if that was my parent that was getting dragged out of my house, I can guarantee you that my life would have been a shambles.” Here, Rihanna alerts us that Guyanese women face deportation in Barbados and are seen as foreign menaces. In order for the Barbados government to celebrate Rihanna as a national hero and as a symbol of Bajan tourism, it has had to ignore the superstar’s Guyanese ancestry.

There are Guyanese immigrant communities living around the globe, from London to Toronto. You mentioned that Guyanese immigrants represent New York City’s fifth-largest foreign-born and third-largest Caribbean-born population. Interestingly, women are disproportionately represented in New York, outnumbering men at a ratio of 100 to 79. How are Guyanese women making their mark in New York and around the globe?

Guyanese women’s larger numbers in New York are an apt indicator of their presence across the global Guyanese diaspora in which women are at once central and invisible: if we look closely, we see them as leaders in artistic production, entrepreneurship, and activism, and we witness their objectification across popular registers.

As a child, Rihanna spent time with her Guyanese grandmother in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn. There, RiRi would have been witness to the outsized presence of Guyanese in the borough. In the book, I make the case that Rihanna’s song, “Birthday Cake” is a clear nod to the Guyanese creole term for vagina, “pattacake”—the word Guyanese mothers use when teaching their young daughters about their bodies. That song is now a birthday anthem at Miss Lily’s, a popular Caribbean restaurant with outposts in New York City, Negril, and Dubai. So even though Miss Lily’s is not owned by a Guyanese woman, Rihanna’s sonic presence provides the soundtrack for the restaurant.

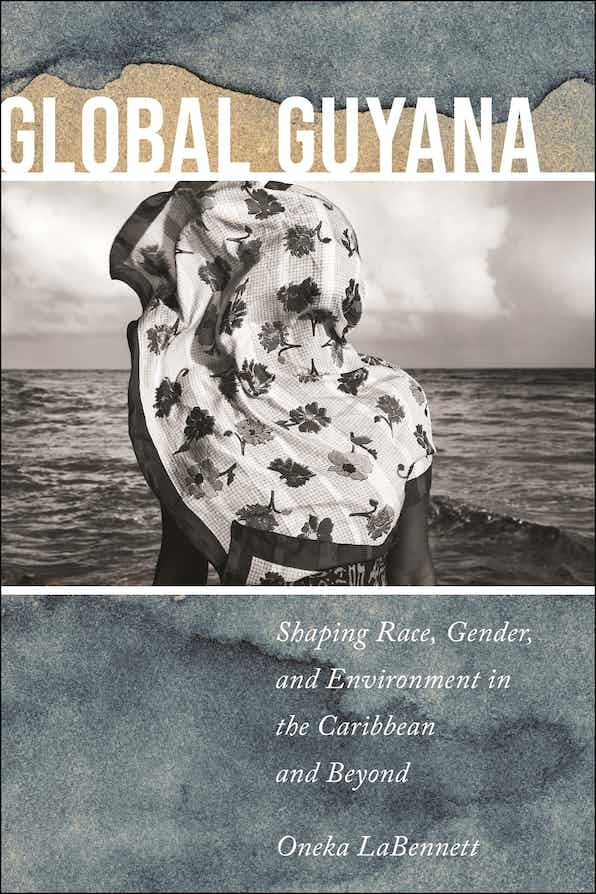

And we know that “Little Guyana” in Queens is the home of a multitude of Guyanese eateries, many of them women-owned or founded by women, such as Sybil’s Bakery and Restaurant, which also has a location in Flatbush. Also in New York, Guyanese women such as the curator/scholar, Grace Aneiza Ali (author of Liminal Spaces: Migration and Women of the Guyanese Diaspora) and the photographer, Keisha Scarville (whose photograph, “Within/Between/Corpus” is the cover image for Global Guyana), are leaders in the global art scene.

All too often, we overlook the Guyanese ancestry of famous women such as Shirley Chisholm, who was the first Black congresswoman and the first Black woman to run for president of the United States (her father was born in Guyana), or the celebrated actress CCH Pounder (who was born in Guyana, and starred in NCIS: New Orleans, Avatar, and HBO’s Full Circle, which portrayed Guyanese immigrants in New York City). Globally, Guyanese actresses are increasingly visible—there were two Guyanese actresses in Black Panther! The blockbuster franchise stars Letitia James (who played Shuri in Black Panther and took on the lead role in the sequel, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever), and Shaunette Renée Wilson (who starred in Fox’s The Resident and played a member of the warrior women—the Dora Milaje—in Black Panther).

What is a pointer broom? How does this metaphorical image represent women’s lives in Guyana?

The pointer broom, or “pointa” broom is a handleless Guyanese yard broom traditionally homemade from the dried spines at the center of coconut leaves, then tied in a tight bundle with a small strip of cloth or twine. It is an everyday tool that generations of Guyanese girls and women have used to sweep up dust, sand, and debris in yards and homes. With continuous sweeping, the dried spines truncate, rendering the instrument shorter and shorter and necessitating that the sweeper bend closer to the ground, repeatedly stamping the top of the broom against a hard surface in order to realign the individual spines. The Anglophone Caribbean saying “new broom sweep clean, but old broom know corna” positions the broom as a metaphor for the value of experience and as a symbol for recovering the past. With origins in Africa and Asia, the “sweep, sweep, stamp” of the pointer broom resonates across the Caribbean and the African and Indian diasporas. The kinetic interplay between sweeper and broom mirrors the movement of women and resources across continents, and reverberates in the transnational sonic routes of African Diasporic music.

The women in my family coil their pointer brooms in suitcases, bringing the brooms along when they settle in other countries. Wielded in a sweeping motion, the pointer broom becomes an apt metaphor for my approach in Global Guyana, which is both gendered labor and a historiography that susses out morsels of cultural knowledge and history that have long fallen into seemingly inaccessible cracks and crevices. The pointer broom approach positions Guyanese girls’ and women’s understandings of their own social worlds as uniquely efficacious for uncovering a more nuanced ethnographic engagement with Guyana. My pointer broom analytic employs a number of interdisciplinary methodologies, including autoethnography, archival research, and oral history, to offer an unconventional portrayal of “the land of many waters” and its global connections. My reliance on autoethnography, a genre that eschews the traditional anthropological fallacy of the distanced researcher, was once virtually tabooed in the discipline. Autoethnography is now increasingly utilized by scholars within and beyond the field of anthropology. It enables me to place my own genealogy within a social context while destabilizing the tenacious dichotomies between insider and outsider. This approach is most heavily influenced by Black feminist anthropologists, including a trailblazing group of scholars such as Zora Neale Hurston and Katherine Dunham, and a more recent cohort that includes Irma McClaurin, Faye Harrison, A. Lynn Bolles, Leith Mullings, Gina Athena Ulysse, and others. Black feminist anthropologists fuse theory, politics, and the arts, drawing from their own personal identities and experiences to write from perspectives in which the researcher and the “subjects of study” are not separate.

Oneka LaBennett is Associate Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity and Gender and Sexuality Studies at the University of Southern California. She’s the author of She’s Mad Real: Popular Culture and West Indian Girls in Brooklyn and co-editor of Racial Formation in the Twenty-First Century.

Six Classics of Queer Literature

Six Classics of Queer Literature